It is no wonder that the rise of the “creepy kid” movie began in the 1950s with movies like The Bad Seed (1956), which itself came on the heels of teenage angst and rebellion movies like The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

The 50s saw the rise of a new species, the teenager, who was no longer destined to follow in the footsteps of the parent: working the farm, minding the store, heading into the mines, or off to the factory. This new species had something their parents did not have—spare time, and they used that time, at least in the minds of fearful adults, to get up to no good. But surely their sweet, innocent younger children would not do such things…right? Village of the Damned (1960) and its 1964 sequel, Children of the Damned, are quintessential examples of this creepy kid subgenre that is so divisive in horror fandom.

Some love it, others despise it, but there is just something about the idea of such innocent-looking monsters—the contrast of the extraordinarily powerful in the guise of the helpless is simultaneously so compelling and so disturbing.

John Wyndam’s 1957 novel The Midwich Cuckoos was an examination of these kinds of fears, and with its success, a film version soon followed. Village of the Damned, later remade by John Carpenter, adheres to the basic plot of the book, which plays out like an extended version of one of the great episodes of The Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits. One ordinary day, the citizens and animals of the little village of Midwich, England, all fall unconscious simultaneously. For several hours, anyone who tries to enter the village passes out cold. Military personnel on exercises nearby are sent to perform various experiments with similar results. A few hours later, just as inexplicably, the town wakes up apparently unharmed.

Before long, however, it is discovered that every woman in the town capable of bearing children is pregnant by what appears to be immaculate conception, and the pregnancies progress at an alarming rate. Ultimately, twelve children are born on the same day, around the same time, all around the same size, and all with strange eyes.

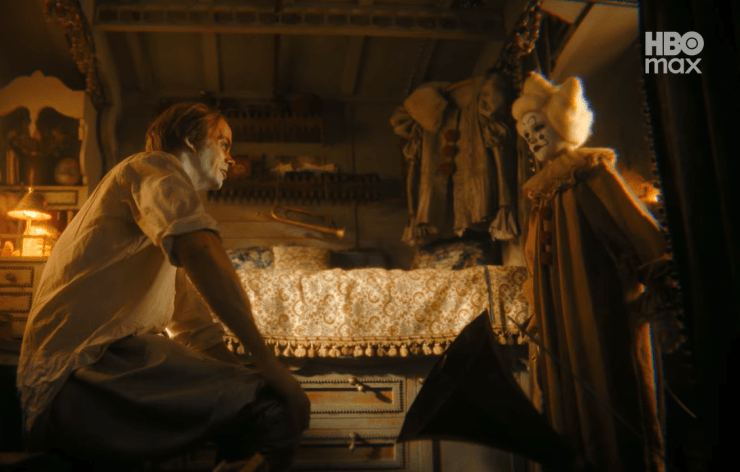

Village of the Damned

It’s a great setup that carries with it several implications about believing women, family planning, freedom of choice in those matters, and societal judgments that existed then and now toward pregnancy in certain situations. Some of the women are unmarried, for example, and all but shunned for their unplanned pregnancies. Another woman is married, but her husband has been away for over a year, and he assumes that she cheated on him. The film presents the unfortunate reality, which remains to this day in many situations, that the burden of responsibility is placed solely upon the woman, with the male counterpart taking none of it. Of course, in this case, the inseminating source of the pregnancies is never discovered. In the novel, it is apparently alien in nature, but neither here nor in Children of the Damned is a definitive answer ever given, though there is much speculation.

After the children are born, they mature quickly, both physically and mentally. Professor Gordon Zellaby (George Sanders), “father” to one of the children, David, takes it upon himself to observe and study the Children. Early on, he discovers that “if you demonstrate something to one of them, they all know it,” which he proves to his brother-in-law by asking several of the children to solve a complicated puzzle box when they are less than one year old. A number of strange accidents also begin to occur around the Children, which only increase as they grow older.

David, now played by Martin Stephens, takes up the leadership of the group of children who have become outcasts in the community because of their strange looks (that iconic platinum blonde hair) and behavior. The Children travel as a group, dress the same, and seem to have no emotion. The children are ostracized, at least at first, for one reason—they are weird. They simply do not fit the societal norms and are therefore bullied, pushed to the margins, and ultimately confined to their own school, which in the real world would be an institution. But still, despite their separation from the rest of the village, the stigmas persist. The fears persist.

The stigma and lack of understanding of the Children are displayed in the actions of the villagers in multiple ways. “They’re not human. They ought to be destroyed,” cries one man whose brother died in a car accident, admittedly caused by the Children as they felt the need to protect one of their own. There are several other “accidents,” but they are all in the interest of self-preservation, and the Children look to the people that surround them as their example. They are cruel, but their cruelty is inspired by those they observe in the village itself. If the people of Midwich had chosen to embrace rather than fear the Children, they would learn they have nothing to fear. In fact, it is apparent that the Children would work with the village for their mutual benefit, given the space and time to learn and grow.

In a scene late in the film, David’s mother Anthea (Barbara Shelley) seems to have this idea in mind when she pleads, “David, why do you do these dreadful things? Wherever it is you come from, you’re part of us now. Couldn’t you learn to live with us and help us live with you?” I believe the answer is an implicit “yes” given the opportunity to mature and cooperation from the people of Midwich, and by extension, the world.

So, where do they come from? What exactly are they? There are speculations about the transference of energy and beams bounced off the moon, but ultimately, it doesn’t really matter. They are here, and they are powerful, which makes them fascinating to some and dangerous to others. It is also discovered that similar events happened around the world at the same time as the Midwich incident, but few of the children survived. Eventually, the Russian government felt its colony had grown too powerful and destroyed the village within its borders with a nuclear bomb, wiping out the entire town, not just the children. Some feel the same thing should happen to Midwich, but Zellaby responds, “What cannot be understood must be put away. Is that your view? The age-old fear of the unknown?” He then goes on to argue that science, society, and humanity itself could be advanced a hundred years by what the children could teach them. But humanity chooses fear instead.

Children of the Damned

These ideas are explored to even greater depth in Children of the Damned, but in both cases, fear overwhelms, and the children are ultimately destroyed by a purposeful act in the original and a clumsy accident in the sequel, making it all the more tragic. Village of the Damned sets the stage and tells a terrific story based on a compelling scenario. Children of the Damned takes that scenario and runs with it, mining the thematic possibilities and expanding it to an international fable of war, peace, and the future of humanity.

In reality, Children is a sequel in name only and more of a reimagining of the concept. There is no discussion of the events of the first film. Instead, it begins with six children born throughout the world with extraordinary intellects by mysterious pregnancy to, as the movie puts it, an “unstable mother and no trace of a father.” These children are all moved to their national embassy within London, where they join forces and hole up in an abandoned church with Susan (Barbara Ferris), sister to one of the mothers, as their guardian and conduit of communication to the outside world.

Again, the people of the world, represented by the adult guardians of the children, argue over whether to destroy them or learn from them. The international element is especially powerful in the mid-60s as the Cold War was at its hottest. The threat of international mutual annihilation was at its height in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962, and as is often observed, genre film can explore social and political issues in entirely unique ways by placing them under the guise of fantasy. The Children each represent a people of the world, all of whom have much at stake in the ever-increasing arms race: Paul (Clive Powell) from Britain, Mi Ling (Yoke-Moon Lee) from China, Nina (Roberta Rex) from the Soviet Union, Aga Nagalo (Gerald del Sol) from Nigeria, Rashid (Mahdu Mather) from India, and Mark Robbin (Frank Summerscale) of the United States. The film depicts these children in perfect harmony, communicating almost entirely by telepathy, while the adult representatives of their nations bicker and build military might.

The symbolism is not subtle.

In the first film, there is a sense of generational fear. The adults dread their destruction at the hands of the Children, which, in a manner of speaking, is true. It is the nature of humanity and life itself that the next generation takes the place of the previous as it ages and dies. In the sequel, the Children fully represent the future of humanity. Though it is not entirely explained, it is postulated that the Children represent an evolutionary leap of at least a million years. Unfortunately, they have learned the bad habit of killing from the adults who attempt to kidnap and destroy them.

Dr. David Neville (Alan Badel) urges them not to kill because they are different, better than the current state of humanity. In a powerful moment, the children stand before the adults who have all the military might of the world pointed in their direction and, through Paul, say, “You have chosen your way, we have chosen ours.” But instead of gaining control of the adults’ minds and forcing them to use their weapons on each other, these children, representing all nations, grasp hands in a moment of solidarity and peace.

But then, through clumsiness and stupidity, the signal to open fire is given, and humanity literally destroys its own future. Again, the symbolism is not subtle, but its power should give us pause. We so quickly fear what we do not understand and seek to destroy it. Instead, we must seek to understand what we fear, or we will be destroyed not by what we fear, but by our own hand. It begs the question, “Who are the real monsters here?”

Yes, the Children are innocent-looking monsters, but we taught them everything they know.

The post Such Innocent-Looking Monsters: The Creepy Kids of ‘Village of the Damned’ and Its Sequel appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.