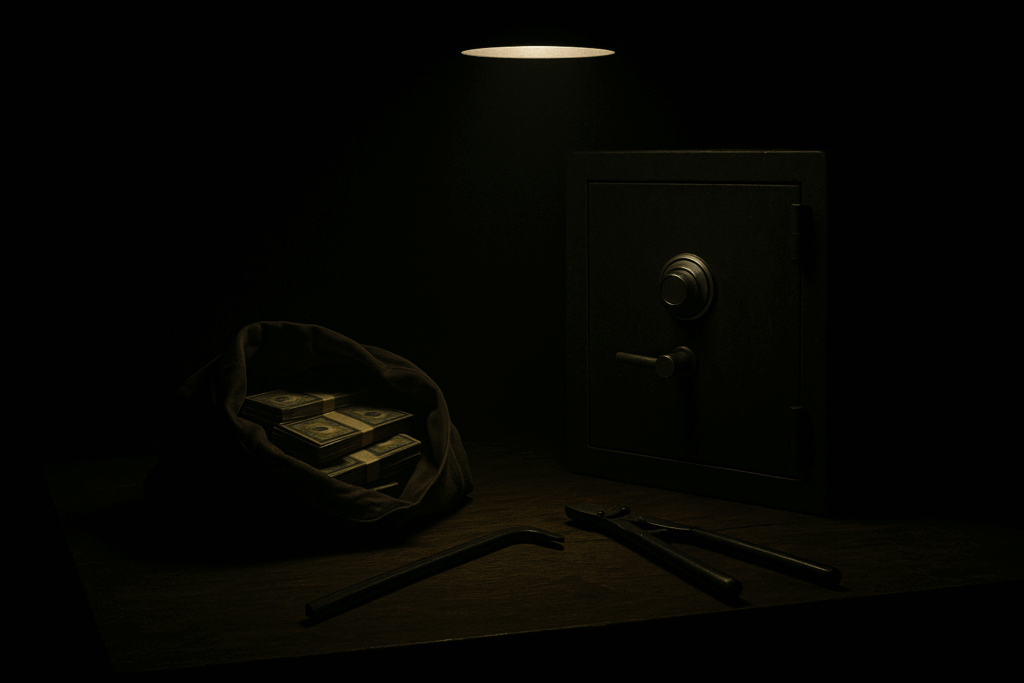

The heist film is one of cinema’s purest pleasures—criminals with a plan, a vault to crack, the tension of everything going wrong. But if you only watch Hollywood’s output, you’d think every heist was a glossy fantasy capped off with a wink at the camera.

American heist films have gotten too clean. You get Ocean’s Eleven knockoffs and weightless CGI action. Nobody sweats. Nobody bleeds. And no one ever seems to care what happens to the money once they’ve got it.

If you want the real good stuff—the heist films that stick with you, that leave you wrung out and wired—look outside Hollywood. International directors understand that a heist should be dangerous, desperate, sometimes absurd, and often doomed. The plans are messier. The outcomes are harder to swallow. The tension isn’t just about the score—it’s about the people doing it, and what the job costs them.

Here’s a list of international heist films that wipe the floor with most of what Hollywood’s cranking out. No smooth-talking con men here. Just sweat, steel, and consequences.

Rififi

France, 1955

It all starts here. Jules Dassin’s Rififi didn’t invent the heist film, but it codified it. The film’s 30-minute silent heist sequence is one of the most copied scenes in cinema history. No dialogue, no score—just the sound of men at work, cracking a jewelry store’s defenses with agonizing precision.

What sets Rififi apart is its understanding that the job itself is just one act of the story. The film has no illusions about the criminal life. The characters are not charming rogues—they’re professionals chasing a score that will ultimately destroy them. Every beat of the film reinforces the futility beneath the craft.

If you’ve ever watched an American heist movie and wondered why everything feels weightless, this is your antidote.

Le Cercle Rouge

France, 1970

Jean-Pierre Melville’s films are built on cool surfaces and simmering tension, and Le Cercle Rouge is his coldest, cleanest distillation of the heist formula. Alain Delon, Yves Montand, and Gian Maria Volonté play three criminals drawn together by fate to pull off a jewel heist.

Melville strips the film of excess. The pacing is deliberate. The characters barely speak. The world they move through feels drained of life. The heist itself is executed with clinical precision, but even success feels hollow. The film’s fatalism is unrelenting: in the world of Le Cercle Rouge, no one escapes their circle.

Hollywood rarely has the patience for this kind of storytelling anymore. Melville makes you live in the silences.

Big Deal on Madonna Street

Italy, 1958

Not every heist movie has to be grim. Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street is a brilliant inversion of the genre—a comedy about a group of small-time crooks trying to rob a pawn shop. They’re out of their depth, underfunded, and perpetually unlucky.

The humor is rooted in character, not slapstick. These men aren’t fools, just desperate and painfully human. The film finds pathos in their failures and joy in their camaraderie. Where Hollywood often glorifies the lone genius criminal, Big Deal reminds us that most heists are pipe dreams chased by guys who should’ve stayed home.

Victoria

Germany, 2015

Victoria is an exercise in cinematic adrenaline: a 138-minute heist film shot in a single continuous take. No cuts. No cheats. You’re locked into the perspective of Victoria, a young Spanish woman who gets swept into a late-night Berlin heist with a group of strangers.

What makes Victoria special is its escalation. The film starts as a slice-of-life hangout movie and morphs into a tense, chaotic thriller. The characters don’t fully understand the job they’re committing, and neither do we. When it goes wrong—and of course it does—you feel every second of the collapse.

The one-take gimmick isn’t just a trick here. It traps you in the moment, forcing you to experience the mounting dread in real time. No Hollywood film has pulled off this kind of raw immediacy in a heist narrative.

Cash Truck (Le Convoyeur)

France, 2004

Forget Wrath of Man. The original Cash Truck is leaner, meaner, and far more interested in the psychology of its protagonist. Albert Dupontel plays a new security guard on an armored truck team. As the film unfolds, we learn he has his own reasons for taking the job—and they aren’t good.

Director Nicolas Boukhrief uses the routines of the armored truck business to build tension. The monotony of the job makes the bursts of violence hit harder. The film’s heist sequence is brutal and grounded, with none of the bulletproof-vest fantasy you get in American action.

It’s a cold film about cold people doing dangerous work. No style for style’s sake. Just blood and consequence.

El Aura

Argentina, 2005

Fabián Bielinsky’s El Aura is one of the most hypnotic heist films you’ll ever see. Ricardo Darín plays an epileptic taxidermist who stumbles into an opportunity to pull off a major robbery. He’s brilliant but socially disconnected, and his seizures threaten to unravel everything.

What makes El Aura so gripping is its mood. The film isn’t about a flashy score—it’s about a man wrestling with his own fragility while trying to impose control on an uncontrollable world. The heist elements are tangled up with existential dread.

It’s the kind of film Hollywood rarely attempts—a slow-burn character study with a crime story at its core.

No Tears for the Dead

South Korea, 2014

Korean cinema is unmatched at blending genre conventions with emotional depth, and No Tears for the Dead is a prime example. Jang Dong-gun plays a hitman assigned to clean up the aftermath of a botched heist. His target: the young daughter of one of the victims.

The action is brutal and impeccably staged, but what elevates the film is its focus on guilt and redemption. The protagonist is a broken man, and the violence he commits feels ugly and personal. The film’s climactic shootout is one of the best in modern cinema—messy, tense, and exhausting.

Where Hollywood heist films often treat gunfights as spectacle, No Tears makes every bullet count.

Time and Tide

Hong Kong, 2000

Ringo Lam’s Time and Tide is a chaotic, kinetic hybrid of heist film and action thriller. The plot barely matters—a bodyguard and an ex-mercenary get tangled in a heist gone wrong—but the energy is relentless.

Lam’s direction is pure Hong Kong madness: handheld shots, impossible angles, and stunts that look genuinely dangerous. The film doesn’t fetishize the mechanics of the heist. It’s about momentum, about what happens when plans dissolve and survival becomes the only goal.

No Hollywood film matches this kind of raw, physical filmmaking anymore. Time and Tide reminds you what action can feel like when it’s shot with bodies, not pixels.

The Silent Partner

Canada, 1978

A perfect little gem of a thriller. Elliott Gould plays a bank teller who figures out that a masked robber (Christopher Plummer) is about to hit his branch. Instead of alerting the cops, he skims part of the take for himself—and triggers a terrifying game of cat and mouse.

The Silent Partner is a masterclass in tension. The heist itself is just the opening move. The real thrill is watching two intelligent, ruthless men try to outmaneuver each other. Plummer’s performance is ice-cold, and the film never lets you relax.

It’s small-scale, focused, and utterly ruthless—a reminder that a great heist movie doesn’t need a massive budget or an ensemble cast.

Quick Change

USA/Canada, 1990

Okay, technically this one’s American/Canadian—but it belongs here. Quick Change flips the heist formula by making the getaway the entire movie. Bill Murray robs a bank in clown makeup and pulls off the perfect crime. The hard part? Escaping New York.

What follows is a dark comedy of escalating obstacles. Every simple task—finding a cab, getting to the airport—spirals into chaos. The film is hilarious, but there’s a simmering anxiety beneath it all. You feel the city closing in, the clock ticking down.

Quick Change understands something most heist films forget: the escape is where the tension lives.