Horror legend John Carpenter turns 78 this Friday, and Halloween Night: John Carpenter Live from Los Angeles is now streaming on Screambox. Bloody Disgusting is celebrating with John Carpenter Week. Today, Matthew Jackson examines the scariest scene in Carpenter’s filmography.

It takes nearly an hour for the scariest scene in John Carpenter‘s filmography to emerge from its home film, Prince of Darkness, and when it finally does arrive, it feels at first like it doesn’t fit at all.

Prince of Darkness, the middle entry in what Carpenter has loosely termed his “Apocalypse Trilogy,” emerges from a satisfyingly pulpy, old-school weird fiction premise. In the very simplest terms, it’s a movie about Satan in a jar buried beneath a random church in Los Angeles, a fun idea that allows Carpenter to play with religious horror, possession, and even science fiction. By the time the scariest scene emerges, it already feels like a complete story barreling toward a confrontation with unimaginable evil.

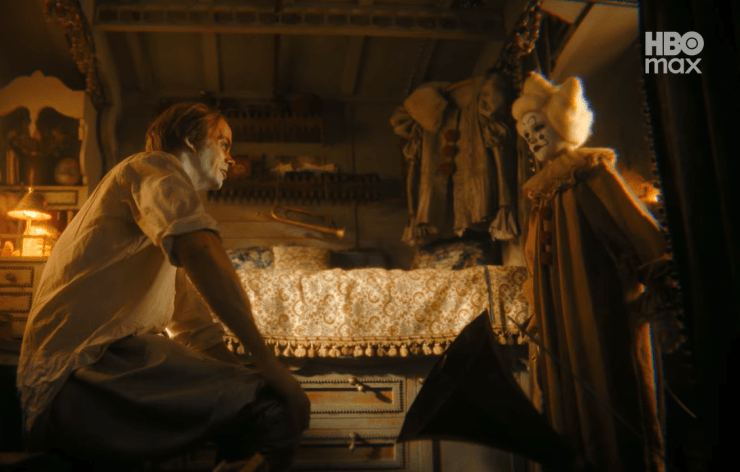

Then this happens:

If it’s your first time with Prince of Darkness, you’d be forgiven for thinking that you missed something, or something went wrong with your player. It feels like you’ve clipped out of one film and into something else, something that feels more like a vestigial piece of VHS tape than a scene in a movie. It arrives completely with fanfare, without windup, and disappears just as quickly as Walter (Dennis Dun) wakes up with a jolt on his cot. It’s so quick, and so strange, that you almost don’t notice that it’s footage of the very church where Carpenter’s band of scientists is holed up, searching for answers to contain evil incarnate.

Then it happens again. And again. Finally, the Priest (Donald Pleasence) presiding over the whole operation explains that the monks who called this church home, the Brotherhood of Sleep, have shared this dream for years. Anyone who falls asleep inside the church and its adjoining monastery experiences it, but no one knows exactly what it means.

So, what makes this so frightening? We begin with the simple truth of all nightmares: You are not in control. The team deduces that, as the voice in the message suggests, it’s not a dream but a transmission from the future using tachyons, upping the sci-fi factor in the film, but that doesn’t change the mechanics. Just as Wes Craven invented a demon who traffics in the murder of sleeping youths, Carpenter has invented an apocalyptic prophecy that beams into your head whether you like it or not. We all must sleep, and these people must stay in this monastery, and so they must confront the message, over and over again, no matter how confounding and eerie it feels.

No matter how many times you see it, the scene is irrepressibly, confoundingly eerie in a way that nothing else in Carpenter’s entire body of work can mimic. Carpenter’s beloved anamorphic widescreen lens is gone, replaced by grainy images that look more like something from a camcorder. The images are recognizably the same church, with the same iron fence, the same sign, the same statuary. But it’s not a carefully composed image, or at least it doesn’t appear to be.

Carpenter’s camera slinks low as the voice attempts to transmit a message, a voice that croaks with static like the robotic updates that come through an old weather radio. It feels, as the camera shakily creeps along the fence, that we’re meant to be hiding from something. It mimics that particular nightmare scenario in which we know that we’re meant to be afraid of something, but we can’t quite see it. We long to see it, long to understand it, and thus loosen fear’s grip, but it’s just out of reach. Which brings us to the finale of the sequence, each time it appears: A figure draped in a ragged cloth, silhouetted in pale light, ready to emerge from the church doorway. It’s an image you will never, ever forget, particularly as its meaning drills down into you throughout the rest of the film.

Prince of Darkness largely unfolds within the confines of the church, but every peek at the wider world suggests a change initiated by the strange container in the monastery basement, the ancient prison filled with Satan’s energy. The Priest talks about the sun changing, the air growing colder, and outside in the alleys and the parking lots, a host of drones in service to this dark energy have gathered. Unhoused people, stray passers-by, even reanimated corpses packed with insects lurk, waiting as the container leaks, spreads its malefic force. The context for the jarring dream/message grows clearer: Whatever is emerging from that church is the end of all hope for humanity, unless these scientists can stop it.

Knowing this, understanding that every time you close your eyes, this vision of emerging evil will haunt you, is frightening enough, but as the film nears its conclusion, Carpenter adds an element of more emotional, less existential investment. Throughout the film, fellow scientists Brian (Jameson Parker) and Catherine (Lisa Blount) have fallen for each other, sleeping together before their scientific mission begins, and then putting off what’s clearly a real emotional connection until the stakes are so impossibly high they simply have to admit how they feel, so they don’t have to die with it unsaid. The team doesn’t successfully contain the evil in the cylinder, but when Catherine sacrifices herself to push it and the “Anti-God” it seeks to summon into the dark dimension from whence they came, Brian is left deeply scarred by the experience. The world might be saved, but his future will forever be one different from what he’d hoped.

The film seems to head toward its ending without ever addressing the mysterious dream messages again. We never learn exactly who sent them, or exactly how, or what’s happening to lead to this moment when the evil force emerges from the church. All we know is what it implies, so when Brian dreams, from his own bed back at home, of Catherine emerging from that pale doorway in some future transmission, he wakes in a cold sweat. The implication is clear, and it’s one of the darkest in Carpenter’s filmography: Evil does not disappear. It cannot be banished, cannot be truly wiped away. It can only change forms, bide its time, tempt us with visions of what we truly want. The dreamy visions of evil triumphant have broken containment. They no longer belong solely to the Brotherhood of Sleep. For all we know, they could be everywhere.

It’s not as flashy as The Thing or as iconic as Halloween, but Prince of Darkness‘s daring dream transmissions are as indelible and potent as anything else in his filmography. They emerge as something seemingly incongruous, and though they quickly become part of the larger narrative, they still stand out as works of art unto themselves. These dark, grainy prophetic snippets of footage are the closest Carpenter ever got to the inexplicable yet inescapable logic of true nightmares, and they deserve to be remembered that way.

Follow along all week long as we salute John Carpenter.

The post This is Not a Dream: Looking Back at John Carpenter’s Scariest Scene appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.